In April 1940, as Europe descended into war and America resisted being drawn in a fight that was “over there”, a shipment of sophisticated navigation watches quietly made its way from Switzerland to Japan via American channels. These were Longines Weems Second-Setting models, designed for the United States military by an American admiral and soon to be on the wrists of Japanese aviation navigators who were preparing for one of history’s most pivotal military operations.

Within a few months, in ‘a date that will live in infamy,’ Japanese pilots executed a meticulously planned surprise attack, navigating across the Pacific while maintaining strict radio silence and relying solely on visual navigation to bomb Pearl Harbor, ultimately ‘awakening a sleeping giant’ and propelling America into the guts of World War II. All of this arguably impossible without the aid of these watches.

In a peculiar twist of pre-war commerce, these watches took a circuitous route to reach Japan, they were not shipped directly from Switzerland, but ordered by Wittnauer, Longines US distributor, and subsequently purchased in American Jewellers by what we assume were people posing as Japanese tourists.

Today, fewer than twenty examples of these Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) watches are known to exist, making them some of the rarest known military timepieces. Each piece is a witness to a decisive moment in history, when the skies above the Pacific were to become a theatre of devastating aerial warfare.

The story of Japan’s military timepieces begins not with Longines, but with Kintaro Hattori, known as the “King of Timepieces in the East.” In 1886, Hattori began importing Swiss and American watches directly into Japan through his company, Hattori & Co., quickly becoming one of Tokyo’s largest watch sellers during the Meiji era.

Hattori’s ambitions extended beyond mere distribution. In 1892, he opened the Seikosha factory, producing Japan’s first domestically manufactured pocket watch, the Time Keeper, three years later. His approach combined shrewd business acumen with technological pragmatism, what he termed “technological hybridization”, borrowing the best elements from Swiss precision, German innovation and American mass production models.

The operation ran at a loss for nearly two decades, subsidized entirely by profits from importing the very Swiss watches Hattori was learning to copy. By 1910, Seikosha was the only company still making pocket watches in Japan. The company didn’t break even in manufacturing until 1913[4], the same year it produced Japan’s first wristwatch, the enamel dialed ‘Laurel.’

Hattori had established an agency relationship with Longines as early as 1911, importing thousands of their movements. His success came partly through Japanese customs protectionism but equally through technological adaptability, studying imported watches to improve his own production methods.

When the 73-year-old founder passed away in 1934, Hattori & Co. had become the world’s largest watch producer, with factory output surpassing its main Swiss and American competitors.

By 1933, Hattori’s watches had achieved quality equal to or sometimes exceeding their Swiss counterparts, according to internal reports by the Allgemeine Schweizerische Uhrenindustrie AG (ASUAG), the holding company controlling production of Swiss watch movements. This assessment was confirmed through expert testing conducted in Le Locle on fourteen watches, including nine from Hattori’s factories. The Swiss embassy in Tokyo secured samples for additional testing in January 1934, which confirmed the earlier evaluation.

As Japan’s imperial ambitions grew in the 1930s, so did the military’s demand for specialized equipment. In 1937, Hattori established a subsidiary, Daini Seikosha Co., specifically to meet the needs of the Japanese military. Production peaked in 1940 at 1.3 million units, with the company originally supplying five issued models for each branch of service.

The three military branches were originally supplied base metal chrome plated manual wind watches with different dial notations; an anchor for the navy, a star for the army, and a cherry blossom for the air force. The aviation models notably featured hands and dial markings with radium for nighttime visibility.

Credit for Japan’s rapid advancement in precision engineering during this period must also be given to Professor Aoki Tamotsu, who headed the Tokyo University Department of Arms Production (zohei gakka), the so-called DAP, until it was renamed the Department of Precision Engineering (seimitsu kikai kogakka) in 1945. Recognizing the need for specialist horology training, Aoki headed the Precision Industry High School (Koto seimitsukogakko), co-founded in 1933 by the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Tokyo and the Horological Institute of Japan (Nihon tokei gakkai).

Professor Aoki became one of the primary drivers of dramatic engineering improvements across Japanese industries after conducting an extensive study tour in 1935, visiting 84 international factories during a five-month trip. His influence was particularly significant in emphasizing the need for production engineers in various key industries, including precision watchmaking.

By 1943, Daini Seikosha had produced 500 marine chronometers, effectively copying the Ulysse Nardin pieces that the military had purchased in the 1930s. The company dramatically expanded its employment of specialist production engineers, developing the technical capability to produce these high-precision instruments domestically.

The Seikosha factory production facilities were destroyed at the end of WWII, later rebuilt, and today the Seiko brand is an international juggernaut, and one of the most recognized international global brand names in the world.

Evidence suggests that all watches for the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service were issued with consecutive numbering. The highest known Longines Weems IJNAS number is #1403, while the lowest Tensoku seen is #1474, supporting the theory of consecutive numbering across different models. Issue numbers on the Tensoku have been observed as high as 7xxx, and during the precarious final months of the war in 1945, some Tensoku watches were supplied without numbering at all.

Whilst the exact production number remains a mystery, estimates based on known numbers of all IJNAS issued watches put production at less than 10,000. Which Japanese air units were issued them, who added the Kanji markings to the back, and where they saw action still await discovery.

Originally, the watch developed a reputation as a model for Kamikaze pilots among early collectors. Whilst this is possible, and likely for some, we know that they certainly saw action in other theatres of war in the Pacific and that only a small handful of pieces have survived.

This imposing watch featured a manual-wind movement originally derived from a 19-ligne pocket watch caliber. With applied radium on both hands and dial, a rotating bezel that controlled an inner chapter ring, and a large onion crown designed for use with gloves, it was purpose-built for military aviation. The case was made of chromed nickel, likely chosen not only due to material availability and manufacturing limitations during wartime, but also because Seikosha lacked the necessary tooling to work with stainless steel, which was protected by Swiss patent #138647 from 1934.

As rare as the Seikosha Tensoku is, it is not the scarcest of all timepieces supplied to Japanese military forces in World War II. That distinction belongs to the Longines Weems models delivered to the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) between 1937 and 1940 which predates the manufacturing of the Tensoku.

They had an unusual procurement path. Rather than being ordered directly from Switzerland, they were acquired through the American agent Wittnauer, just as tensions between Japan and the United States were rising.

The last IJNAS Weems delivery is made June 21, 1940 which coincides with the introduction of the large brass nickel case Seikosha Tensoku watches which were first delivered in 1940/1. The Hattori company were importing Swiss watches from 1886, had a longstanding agency and import relationship with Longines from 1911.

The latter’s prowess and history in making aviation pieces and the accuracy and precision of their movements was well known. However, this was only one consideration for the Japanese and Hattori & Co in the selection process.

Longines were the only maker of the large Weems model, had the technical equipment, technology and available materials for making the steel watches the Japanese received in 1940.

Steel watches were rare in the 1930’s and whilst some Longines steel chronographs were known to be delivered directly to Hattori in October 1935, the patent for staybrite steel was owned by Thomas Firth John Brown Ltd, of Sheffield, and protected by Swiss patent #138647 from 1934.

The Weems used the pocket watch base calibres 18.69N and 37.9 at the time of Japanese deliveries. Daini Seikosha were not involved, nor interested in innovation. Earlier copying and modelling of Longines movements, alongside watch making machinery by Hattori confirmed this. Given Hattori skills were significantly developed in this manufacturing space, having made their first pocket watch in 1895, it is highly likely they wanted a model on which to base their Tensoku aviator watch.

The Japanese have no equivalent word for Air Force, and the caseback of both the Seikosha pilot and the Longines Weems pieces feature Kanji characters (空兵). This literally translates to ‘Air Soldier’, along with a Japanese character for dai (a prefix for number), with the actual issue number.

The Longines Weems IJNAS watches were produced in two distinct variants:

The first generation, delivered on September 17, 1937—just two months after the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War—featured solid silver cases and the robust 18.69N pin-set caliber, reference 5350. These pieces are exceptionally rare, with Longines records noting production of fewer than fifty units. Over the past 25 years, only three documented examples of this model have surfaced (Air Soldier #121, #131, and #143). On this first model, the Kanji characters run in a single line down the middle of the case back, differing from the arrangement on later models.

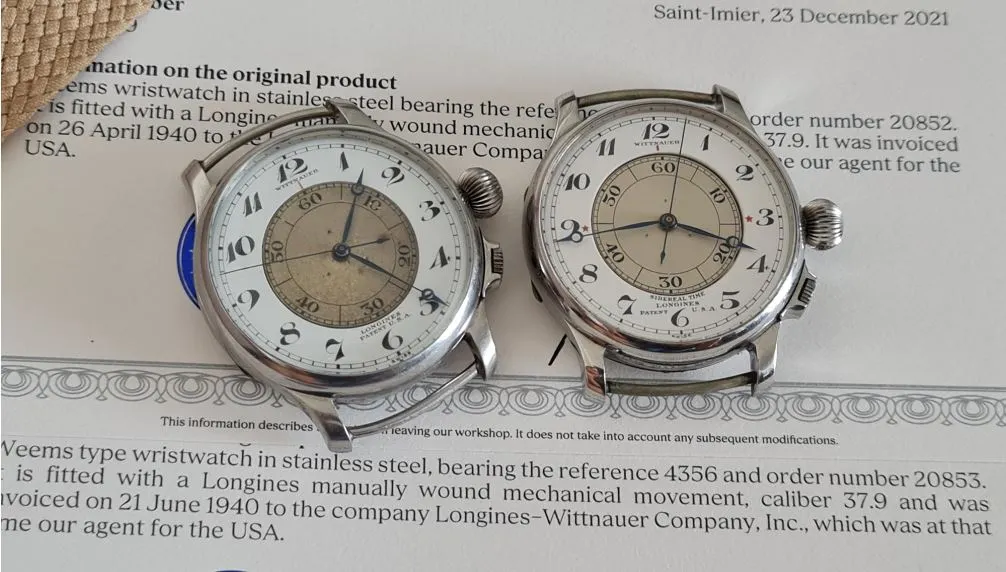

Steel cases for Weems and Lindbergh models first appeared in 1938, although silver cases continued to be used into the early 1940s for some Lindbergh Hour Angle watches. The second iteration of the IJNAS Weems, delivered in 1940, used steel cases and the 37.9 caliber with a second crown at four o’clock to adjust the second-setting function. These Type A-12 military designation pieces (reference 4365) were regulated for either sidereal or civil time and delivered on at least three separate dates in 1940.

Steel watches were particularly rare in the 1930s. Notably, some Longines steel chronographs were delivered directly to Hattori in October 1935, but the patent for “Staybrite” steel was owned by Thomas Firth John Brown Ltd of Sheffield and protected by Swiss patent #138647 from 1934. This technological limitation, combined with wartime material shortages, influenced the manufacturing choices for Japanese military timepieces.

The first batch, regulated for sidereal time, arrived in the USA on April 26, 1940 per order #20852, while a second batch adjusted for civil time per order #20853 followed shortly after. Both orders comprised approximately 200 pieces each. When supplied, the sidereal time models featured two red stars at 3 and 9 on the dial to indicate adjustment for star time. Interestingly, on almost all known surviving examples, these stars have been removed or damaged, possibly due to post-war concerns about communist symbolism during the McCarthy era.

The consecutive order numbers for these different time regulated watches suggest they were intended to be used together. Sidereal time watches are typically employed alongside timepieces running civil time for celestial navigation.

These IJNAS Weems watches were used by Japanese “Air Soldiers” in various theatres of war in the Pacific. Early pre-WWII aviation and the war itself was a very dangerous game with a short lifespan for many participants, especially pilots. Consequently, early aviation watches, especially military issued ones are highly sought after by collectors.

The Longines Weems IJNAS watches came in two distinct variants:

Delivered on September 17, 1937—just two months after the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War—these featured solid silver cases and the robust 18.69N pin-set caliber, reference 5350. Longines records indicate production of fewer than fifty units. Over the past 25 years, only three documented examples have surfaced: Air Soldier #121, #131, and #143. On these models, the Kanji characters run in a single line down the middle of the caseback.

By 1940, technological advances allowed for steel cases—though “Staybrite” steel remained protected by British patent and Swiss patent #138647. These Type A-12 military designation pieces (reference 4365) used the 37.9 caliber with a second crown at four o’clock for the second-setting function.

The 1940 deliveries included watches regulated for both sidereal and civil time. The first batch, regulated for sidereal time, arrived on April 26, 1940 (order #20852). A second batch adjusted for civil time (order #20853) followed shortly after. Both orders comprised approximately 200 pieces each.

The sidereal time models featured two red stars at 3 and 9 o’clock on the dial. Intriguingly, on almost all surviving examples, these stars have been removed or damaged—possibly due to post-war concerns about communist symbolism during the McCarthy era.

Japan’s rapid aviation development owed much to foreign expertise. After World War I, Japan was recognized as one of the three greatest naval powers alongside Britain and the United States. Under the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, Japan accepted tonnage limitations but realized that they were lacking in skills and experience in the naval aviation space, and wanted to improve their naval air arm.

To accelerate this development, Japan enlisted Captain William Forbes Sempill, who led a British mission arriving at Kasumigaura Naval Air Station in November 1921. This team of 27 specialists brought more than 100 aircraft representing 25 different models used by the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm. During their 18-month stay, they trained Japanese personnel in aerial weaponry, torpedo deployment, military communications, and carrier operations.

Some of the planes would provide inspiration for Japanese designs that followed and whilst Japan was still dependent on England for much of the 1920’s, it was in the process of developing an effective naval air force.

Following the London Naval Treaty of April 1930, Japan developed naval construction plans known as hoju keikaku. Four “circle plans” (maru keikaku) were formulated in 1931, 1934, 1937, and 1939, creating the formidable Imperial Japanese Navy.

The Second Sino-Japanese War provided the first major testing ground for these forces. Japanese naval carrier aircraft attacked installations along the Yangtze River and bombed Chinese cities deep in the interior, the first time any naval air arm had been assigned strategic bombing missions.[12]

Given Japan’s involvement in WWII from July 1937, it struggled with ongoing raw material supplies. Typically, military watches are made in quantity, and from available and at times lower grade materials. In the early stages of war, materials and watches were more available. However, not all not all Imperial Japan military personnel were issued timepieces and given the eight years of war for Japan, material supply issues abounded.

While detailed records of Japan’s military watch issuance procedures from 1937-1945 are scarce, if we look to other countries like Germany and their issuance of military watches, we see the following general rules subject to a few exceptions. Army watches were given to the individual soldier and entered into his soldbuch (identity papers), together with any other equipment he was issued with and they remained Wehrmacht (army/defence force) property. The soldbuch contained passport information, and included extra details about the soldier, including their rank, regiment/unit assigned to, equipment used, issued, and dates of leave.

By contrast, Luftwaffe observer watches (from Laco, Wempe, Stowa, IWC, and Lange) were issued for specific missions and collected after debriefing, then reallocated to the next sortie. This mission-based system was likely employed by the IJNAS for both Tensoku and Weems watches.

The markings on the British Army watches were done by the Swiss suppliers whilst the markings on pilot’s watches were added by the Ministry of Defence (MOD). All timekeepers had to be returned to the military once the soldier retired from service.

The absence of historical photographs showing Japanese troops wearing these timepieces, combined with the few surviving examples, suggests both smaller production runs and mission-based issuance rather than permanent assignment.

By December 1941, Japanese naval aviators likely wearing these watches would execute the attack that changed history. The irony remains striking: Swiss precision, funded by American commerce, guided the assault that awakened what Admiral Yamamoto famously called “a sleeping giant.”

Japan’s naval aviation reached its zenith in 1942, controlling vast portions of Asia and the Pacific. But this supremacy proved ephemeral. H.P. Willmott of the Royal Historical Society captured the mathematical impossibility of Japan’s position:

“In 1944 alone the Americans launched a force that rivalled in strength the Combined Fleet of December 1941. Such was the scale of the American industrial power that if during the Pearl Harbor attack the Imperial Navy had been able to sink every major unit of if the entire U.S. Navy and then complete its down construction programs without losing a single unit, by mid-1944 it would still not have been able to put to sea a fleet equal to the one that Americans could have assembled in the intervening thirty months.”

Wartime aviation was dangerous leaving little room for error and often ending in a tragic loss of life for all nationalities. War tremendously accelerated military technology including communications, radio and radar advancements and the need for military aviator’s timepieces.

The numbers are staggering. Japan lost between 35,000 and 50,000 aircraft during eight years of continuous warfare, more than ten times the total aircraft losses of all nations in all conflicts since 1945.[13][14][15] Total World War II aircraft losses approached 379,000 units.

By 1944-45, desperate measures led to Kamikaze units. Between 2,800 and 4,000 pilots made these one-way missions, achieving a reported 19% success rate against their targets.

Flight Lieutenant Haruo Araki wrote to his wife before his final mission:

“Shigeko, Are you well? It is now a month since that day. The happy dream is over. Tomorrow I will dive my plane into an enemy ship. I will cross the river into the other world, taking some Yankees with me. When I look back, I see that I was very cold-hearted to you. After I had been cruel to you, I used to regret it. Please forgive me.

When I think of your future, and the long life ahead, it tears at my heart. Please remain steadfast and live happily. After my death, please take care of my father for me. I, who have lived for the eternal principles of justice, will forever protect this nation from the enemies that surround us.“

While many Kamikaze attacks used stripped-down aircraft that didn’t require navigation equipment, not all such missions were predetermined. Some pilots who departed with full equipment, including their Air Soldier timepieces, made spontaneous decisions to sacrifice themselves when opportunities arose.

By the end of the war technological changes had already largely impacted the need for celestial navigation and the needs for specialist navigators and dedicated timepieces regulated for sidereal time largely disappeared.

Today fewer than twenty known examples across all variants, IJNAS watches stand among the rarest military timepieces ever produced. The three known silver Type A-3 examples are held in private collections from Tokyo to Geneva. The “common” steel variants trade for substantial sums when they rarely surface.

These survivors appear occasionally at auction in Geneva or Hong Kong, usually authenticated by historians, before disappearing into private collections in Japan, Switzerland, or America. The same nations that created, traded, and ultimately destroyed them.

Whilst there may still be the odd piece waiting to be discovered in Japan or America (taken at the end of the war) or lying unknown in a collection. Japanese shop, watch book, auction sales records, and collector pieces over the last twenty-five years, point to fewer than 20 known surviving examples in all three configurations.

In their precision and remarkable survival, these watches are a testament to both the human ingenuity and the terrible cost of conflict. More than mere instruments, they are a tangible connection to young men who flew in a conflict that reshaped our world order.

Seikosha Tensoku (1940-1945)

Known survivors: Approximately 12-15 examples

Longines Weems IJNAS Type A-3 (1937)

Known survivors: 3 documented examples (#121, #131, #143)

Longines Weems IJNAS Type A-12 (1940)

Known survivors: Approximately 10-12 examples

Special thanks to Paul Pfanner for all his help with German and other issued military watches and Allen Wu for his expertise on the Seikosha Tensoku.

Editor Eitan Arrusi

Footnotes:

[1] Seiko Museum online Development of the Japanese Timepiece Industry centered by Seikosha | THE SEIKO MUSEUM GINZA

[2] “The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 361 | Pierre-Yves Donzé — Academia.edu

[3] “The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 361 | Pierre-Yves Donzé — Academia.edu

[4] “The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p | Pierre-Yves Donzé — Academia.edu

[5] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 370 | Pierre-Yves Donzé — Academia.edu

[6] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 370 | Pierre-Yves Donzé — Academia.edu

[7] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 366 | Pierre-Yves Donzé — Academia.edu

[8] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 375 | Pierre-Yves Donzé — Academia.edu

[9] The Department for Arms Production of the University of Tokyo and the beginnings of the Japanese precision machine industry (1930-1960), Osaka Economic Papers, 2011 | Pierre-Yves Donzé — Academia.edu p42

[10] “The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 372 | Pierre-Yves Donzé — Academia.edu

[11] Evans, David & Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

[12] Evans, David & Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

[13] WWII Aircraft Losses By Country — World War Wings

[14] WWII Aircraft Losses By Country — World War Wings

[15] WWII Aircraft Losses By Country — World War Wings

[16] The Divine Wind: Japan’s Kamikaze Pilots of World War II by Author Saul David, PhD | The National WWII Museum | New Orleans (nationalww2museum.org)